On Tequesta, and later Seminole, lands was opa-tisha-wocka-locka, or “high ground amid the swamp on which there is a camping place.” Then the Roaring Twenties and great Florida Land Boom came, and it was swallowed up by a 120,000-acre purchase by the Curtiss-Bright Corporation, which carved from its holdings three cities: first Hialeah and then Country Club Estates (now Miami Springs). The final development of Missouri cattle rancher James Bright and “The Father of Naval Aviation,” Glenn Curtiss, was Opa-locka.

NOTE: A version of this story was published in the Spring 2022 edition of The Florida Preservationist.

Funded by aviation fortunes and built amidst the dizzying speculation of Florida’s land boom, Opa-locka seems at first to fit snugly with other contemporaneous boom cities. But it’s distinguished by the sheer dedication of Curtiss, its patron, who kept the city buzzing almost single-handedly until his death in 1930 at age 52, and its inseparable ties to the aviation industry. It’s an architectural mecca to boot, boasting perhaps the largest collection of Moorish architecture in the Western Hemisphere.

Renowned before ever taking flight, Curtiss’ accolades are far too numerous to list here. A contemporary of the Wright Brothers, Earhart, and Rickenbacker, he was deemed the “Fastest man in the world” in 1907, hitting 136.3 mph in Ormond Beach on a self-built motorcycle. He founded Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company in 1910–the first US licensed aircraft manufacturer–which sold the first US private aircraft before becoming the world’s largest aviation company. He bought out the Wright brothers and formed the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, invented the seaplane, airboat, and “aerocar,” built the first US Navy aircraft, and trained the Navy’s first two pilots. The Wright Brothers held pilots license Nos. 4 and 5; Curtiss held No. 1.

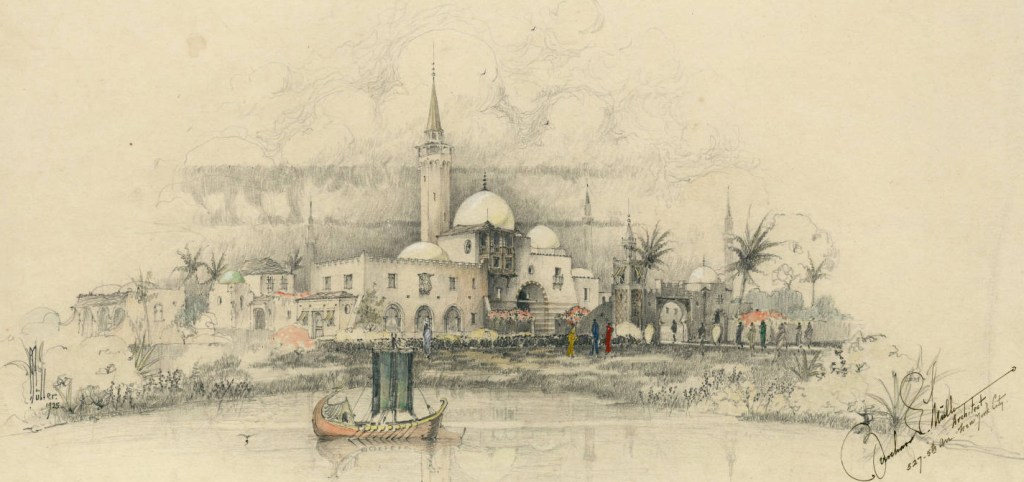

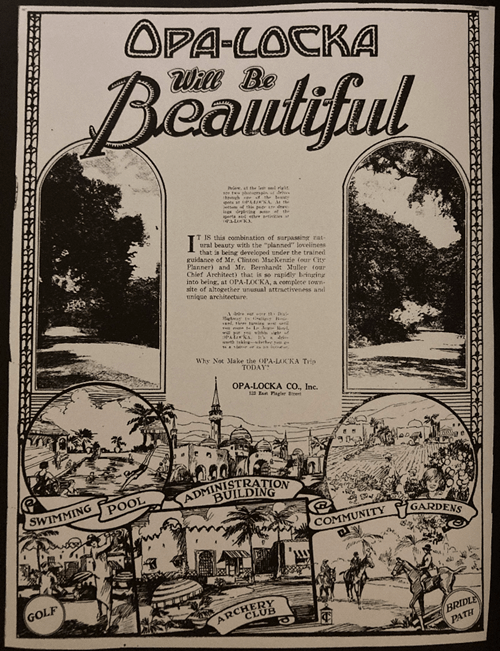

Curtiss retired from aviation to dabble in real estate, commissioning architect Bernhardt Muller to design a city inspired by the Arabic folk tales in One Thousand and One Nights (though the source of the inspiration is disputed). Dedication to this theme transcended architecture; when Seaboard Air Line’s Orange Blossom Special arrived, a band of horsemen in Arabian-themed garb halted the “Great Iron Horse” with a proclamation from “The Grand Vizier of the Empire of Opa-locka,” G. Carl Adams (President of the Opa-locka Company). This event marked the height of the city’s popularity, when it embodied the dream it was advertised to be.

Like other Land Boom cities, Opa-locka relied on relentless advertisement to lure prospective buyers. But Curtiss also employed a literal approach: the town was platted to entice the Seaboard rail line (Curtiss later donated the right-of-way), free busses brought visitors in from Miami, and potential residents were tempted with archery ranges, pools, a zoo, and job opportunities at his local Aerocar plant, for example. His most dedicated passion, though, was aviation.

An airfield for the Florida Aviation Camp opened in 1927 and a dirigible mooring mast was added soon after, hosting the Akron, Macon, and the swastika-adorned Graf Zeppelin; the Hindenburg was scheduled to dock at Opa-locka one week prior to the disaster.

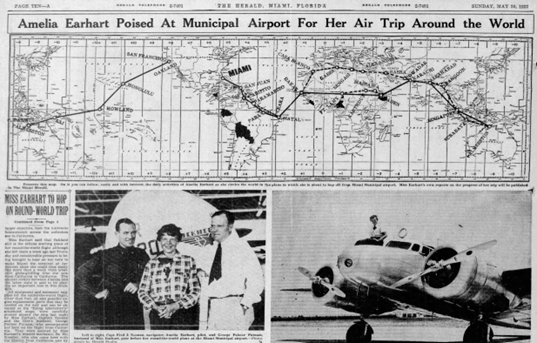

What was called Glenn Curtiss Field would grow into Miami Municipal Airport. In 1937, Amelia Earhart continued her infamous flight from Municipal Airport without her trailing antenna, citing weight issues. On July 2, Earhart and her navigator disappeared over the Pacific. “Municipal Airport” was changed to “Earhart Field” in 1947, but it closed in 1959 and was converted to a switching yard by the Seaboard line.

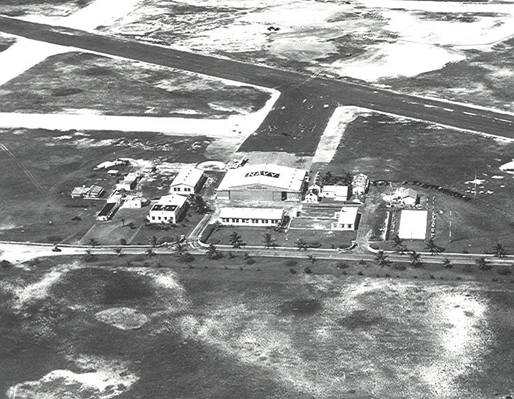

In one of his last acts as Opa-locka’s backer, Curtiss donated land for a Naval Reserve Air Base. By December 1944, then called Navy Municipal and South Field #2, it was the second largest Naval Air Training Station in the US and played a crucial role in World War II. By 1967, Opa-locka was the busiest airport in the US.

Opa-locka’s aviation facilities were central in the CIA’s 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état, the Bay of Pigs invasion and Cuban Missile Crisis, Hurricane Andrew recovery efforts, and 9/11 (two hijackers trained at the airports’ 727 simulator). The blimp hangar even housed Cuban refugees during the Mariel Boatlift. It was blown for the climax of 1995’s Bad Boys.

Opa-locka was devastated by the Land Boom crash and the four catastrophic events of 1926 culminating in the great September hurricane. Newspaper erroneously reported Curtiss and family dead and South Florida swept off the map. Rather, Curtiss almost single-handedly kept the city alive with his dedication and funding. But his death in 1930 was another major blow, the effects of which were partly alleviated by Curtiss’ open invitation to the Navy, which brought jobs and occupants for Muller’s crenulated homes. But the Navy’s expansion continued unchecked, decimating the native hammock that Curtiss had preserved along with over 100 of Muller’s Moorish structures. Following WWII, the Navy retreated from Opa-locka, taking with it the jobs and residents that kept the city buzzing. Lease agreements for vacant facilities were promised, reneged, and promised again, but trust was lost, and the damaging economic effects persist.

City leaders have since dedicated themselves to restoring many of the original structures including the famed City Hall, which reopened in 1987 and is one of 2021’s 11 to Save. The Opa-locka Thematic Resource Area includes 20 surviving Moorish structures that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Returning Opa-locka to its heyday may seem a flight of fantasy, but the dream of Araby came true once before.